Stained Victory

"Never underestimate the power of dreams and the influence of the human spirit. We are all the same in this notion: The potential for greatness lives within each of us."

—Wilma Rudolph, Olympic Track and Field Champion.

Many times, survivors become blind to the accomplishments they achieved while enduring traumatic events. We become so focused on surviving that we overlook what sets us apart. I want to share how I lost sight of something significant in my life and continued to ignore this amazing gift that transpired during my abuse. This is my story of a stained victory.

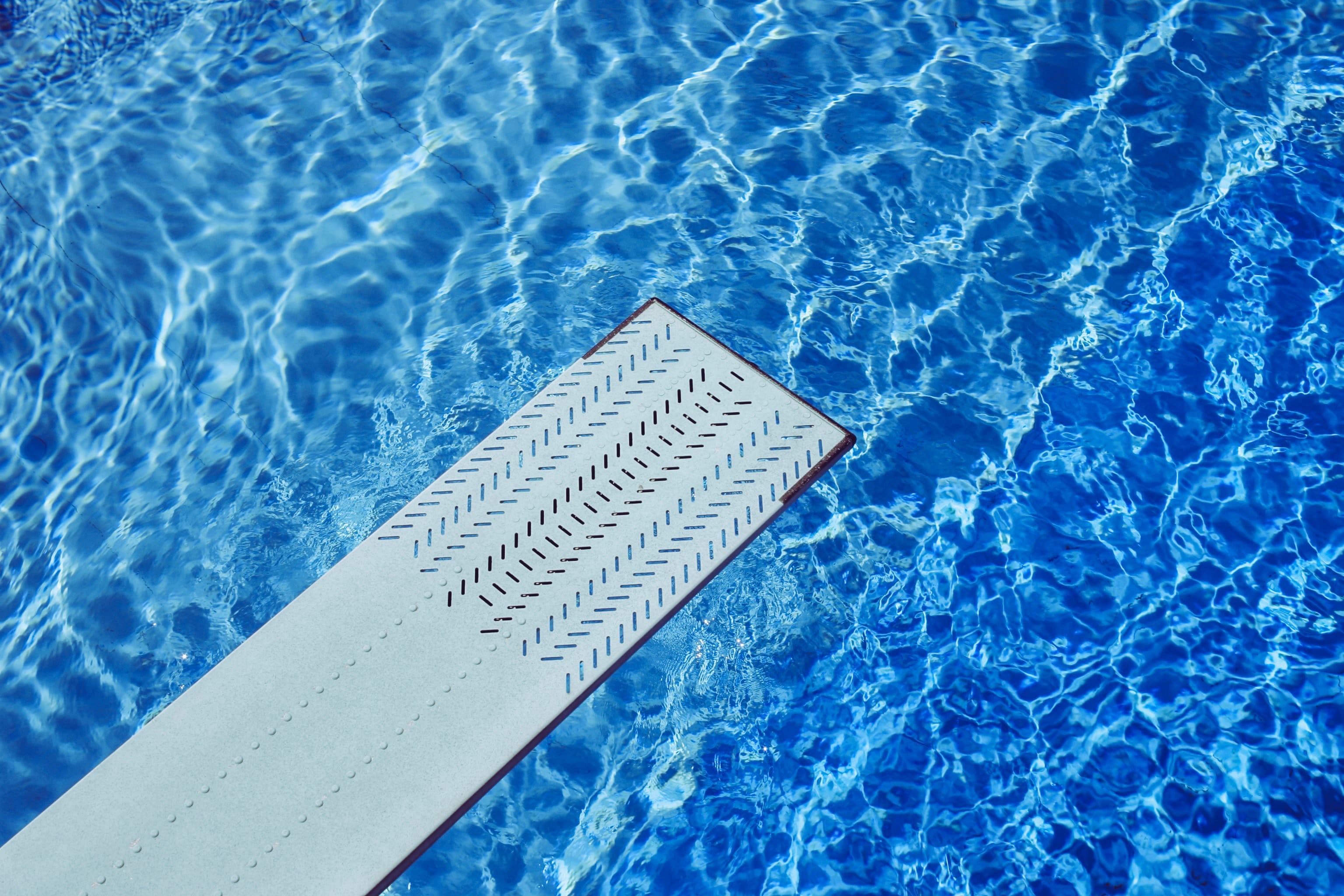

The sold-out bleachers wrapped around the Olympic-size swimming pool of the Sandefjord natatorium and decorated with every nation's flag. The ten-meter platform was the focal point of the diving well, and the massive cement structure towered high above the water with a huge banner stating, "Norway Cup, Tønsberg, Norway" in red letters. The men's three-meter springboard preliminaries were in the last round, and the top twelve finishers would proceed to the finals.

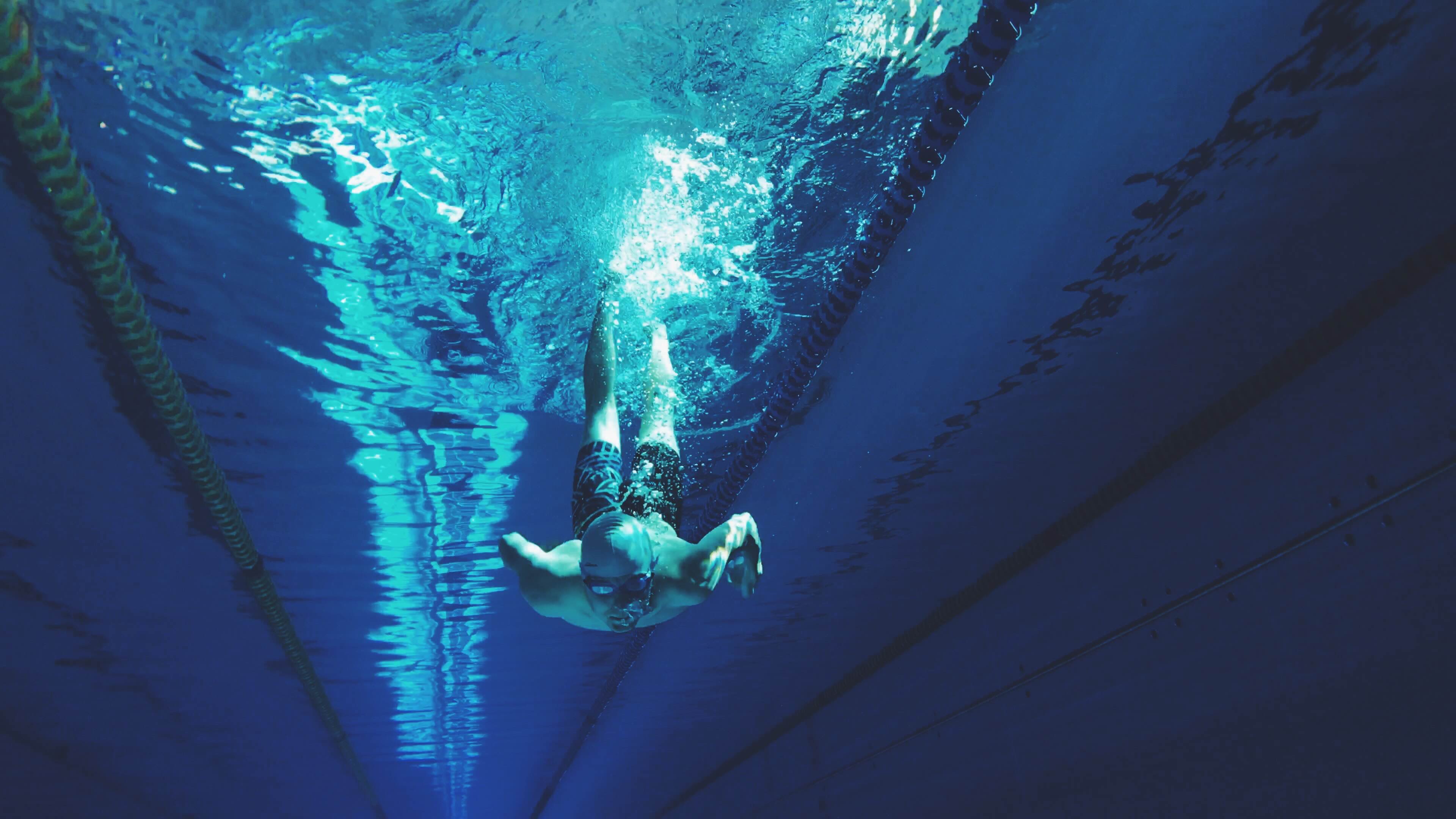

I walked to the nearest three-meter, grabbed the ladder, and rested my right foot on the third rung. Extending my arms over my head, I stretched to the right, left, and forward to stretch my hamstring before switching legs and repeating. I did not want to watch the other divers, so I closed my eyes and rolled my head on its axis. I was confident since I had not missed any required dives in the first four rounds and averaged 8s and 8.5s. I told myself to focus. All I needed to do was get a good compression, wait for the board, extend through my toes, get my arms over my head, touch my toes, check my arms to the side, and stretch for the water.

But the chatter in my mind was louder than ever, and the pressure to perform at my best was at its highest. My chance of being on this team has been an incredible feat, but it may not have happened if it were not for the professionals that offered to help sponsor me for a price.

I was sixteen years old and at my first international diving competition. I should be so excited and thrilled to be here, but I was harboring a dark secret that I could not share with anyone. The adults entrusted with my training had been sexually abusing and trafficking me since I was fourteen—all for this incredible moment to win a gold medal. The shame and embarrassment (when I look back, I can identify with these words, but at the time, I could not label the feelings) weighed heavier than facing the world's best divers. I was numb, yet I still felt this overwhelming pressure that I owed this group of professional men who sponsored and trafficked me.

After the Norwegian diver received his scores, I climbed the ladder. As I adjusted the fulcrum, I glanced at the scoreboard, and what I saw unnerved me. My name was at the top, and I still needed to complete my final preliminary dive. My breath escaped my lungs as if someone had punched me in the stomach. My heart quickened to assist air back into my lungs. My hand trembled, and my vision wavered. I felt I was going to collapse. Somehow a deep breath filled my lungs as if something else had taken over me. My vision cleared as I focused on the end of the board and wiped my fingertips over my Speedo—feeling the stitched USA label on the right-front panel.

My name and dive were announced.

I felt small as I stood on the springboard. I counted at least six television cameras, and their crews focused on me from different locations around the pool and on the platform. The crowd was all posed with countless handheld cameras ready to record this moment.

Silence.

As I walked to the end of the flimsy springboard, turned, and balanced on my toes above the water, my mind began to flash memories like a machine gun. Images of being in a motel 6 with a professional, feeling myself separate from my body, hovering in a corner watching the abuse below, and then being passed to another.

Somehow, I ceased the barrage of images, voices, and sounds in my head. Slowly and systematically, I lifted my arms to the side, rising on my toes. I briefly paused before I swung my arms through, compressed my weight, extended through my legs, and the recoil propelled me up and over the board. I reached and touched my toes, checked my arms to the side, pressed my legs to the ceiling, reached for the water, and streamlined to the bottom of the seventeen-foot depth. I pushed off the bottom, and when I broke the water's surface, I was welcomed with a loud noise that rumbled like thunder throughout the stadium. I glanced at the scoreboard as the scores appeared. Another roll of thunder erupted, replacing the last outburst.

As the reality set in that I not only made the finals, but my score was 100 points ahead of the diver in second place, something within me snapped, releasing the demons to attack. I had a day to figure out how to harness these negative thoughts and images and prepare for the finals. I did not take a breath for the full twenty-four hours. I was spiraling, and there was no one to talk to or share what was plaguing me. I had to figure it out on my own.

Nightmares occupied me throughout both nights before the finals. I felt frail, and dark circles hid my eyes. Everything felt like it was crashing down, and I could not understand what was happening. The next day was a haze, and I tried to pretend everything was normal—but I knew I was lying to myself. Fear replaced my confidence, and I could no longer envision the dives in my head. I felt like an imposter. I was lost, and I could not find my way back. I did everything I could to keep at bay the memories of how I was sponsored and what that all meant.

The finals started, and I was in no better shape. I was in a trance, feeling numb and unable to control my body. I had to be led through the opening ceremonies and introductions. I had to dive last since we went in reverse order of how we finished in the preliminaries. This honor added more pressure and meaning.

Somehow, I automatically went through the motions for my first dive in the finals and to retain my leading position. My head filled with images and thoughts that had nothing to do with diving. Somehow the impacts of the abuse I endured before coming to Norway were up front and center. I became erratic and inconsistent throughout the finals. I missed my second dive for 5s and 6s, and my lead was cut to 50 points. Once again, I missed my third dive, allowing my teammate to take the lead over me by 21.45 points. Somehow, I was granted a reprieve from the demons long enough to perform a dive worth 9s and 10s, which narrowed the gap by 10 points. I cannot remember the next several dives, but as I prepared for my final round, I was again trailing, and the chances of moving up in the ranks were slim to none.

Something happened as I stepped on the metal board for the last time. I felt controlled and focused. The hurdle was high and powerful, and the board's compression was smooth and easy. The recoil sent me toward the ceiling, and my spins were fast. After three-and-a-half revolutions, I saw the water and forcefully kicked out of the tuck position and stretched. I sliced through the water without a splash. It felt good.

When I surfaced, the stadium was dead silent. No one seemed to be moving. I swam to the side, feeling everyone staring at me. Everything was in slow motion and garbled. I felt like I wanted to hide, disappear, even evaporate somehow. It seemed like an entirety. Embarrassed, I grabbed my towels and bag and rushed to the locker room. I was in a void and completely numb. I realized that I wanted to win and not just be here.

The Italian diver asked me why I was hiding and crying. I said that I was not. He told me I should be happy. A roar of excitement and cheers erupted by the pool. The Italian said I should wipe away my tears and see the results.

I somehow won.

After the award ceremony, I found a pay phone to call home. I should have considered that the States were six hours behind Norway. I woke my father up, and when I told him I won, he said, "This is a joke; my son would never win the gold medal," and hung up. Since I was surrounded by the media taking pictures and my teammates, I pretended to have a celebratory conversation with no one.

I went on to win another gold and bronze medal.

Since then, I have put my medals into a display case and hid them behind the couch, under the bed, and even in the closet. I felt this incredible sense of shame, guilt, embarrassment, and anger whenever I looked at them. They represented all the times the professionals abused me and passed me around. I lost the thrill of these medals representing success or victory. I even convinced myself that someone else won those medals—not me.

It was not until I met and worked with award-winning director and producer Barbara McCabe who told me I must get them out of hiding and display them with pride. She created a documentary that helped me see that I did something amazing while being abused.

(198) JML Spotlight v4 Barb McCabe - YouTube

Everyone has something to recognize and celebrate, no matter how small it may seem—it is proof of your power. The idea of surviving the trauma is something to acknowledge and celebrate.

Reflecting on the years I was abused and trafficked, I have found things that may not be significant to others but were beneficial to me and my survival, such as making my bed every morning, which gives me a sense of control and achievement. One survivor shared that she cared for a pet during her abuse and remembered the unconditional love the puppy gave her. Another survivor wrote a book during the abuse and realized that writing was his cathartic tool to help express his feelings.

Take a moment and create a Timeline of a challenging period and write out everything you did, the big and the small events. Allow yourself to recognize and acknowledge the things you accomplished even during abusive times, and you may surprise yourself with all you have accomplished.

About the Author:

John-Michael Lander is a Survivor, Advocate & Public Speaker

He is also the founder of An Athlete's Silence: www.anathletessilence.com

Published by SurvivorSpace, an initiative of Zero Abuse Project