Male Trauma Bonding

Patrick Carnes developed the term, Trauma Bonding, to describe emotional bonds with an individual (sometimes groups) that stems from a recurring cyclical pattern of abuse perpetrated by intermittent reinforcement through rewards and punishment. A trauma bond usually involves a victim and a perpetrator in a unidirectional relationship wherein the victim forms an emotional bond with the perpetrator.

"In Trauma Bonding, trauma fuses a bond between the abuser and victim in which the two replay their original trauma. The abuser asserts his/her power over the victim, causing a life-altering love/hate relationship between them. The victim often experiences this power differential by confusing abuse with a sense of love and caring. When this kind of bonding occurs, victims are in danger of moving closer to the person exploiting them, a very natural and common reaction to trauma."

Kaitlin Casassa (2021) identifies Trauma Bonding as "an emotional attachment between an abuser and victim" with

(1) an imbalance of power that favors the abuser,

(2) the abuser's deliberate use of positive and negative interactions,

(3) the victim's gratitude for positive interactions and self-blame for the negative, and

(4) the victim's internalization of the perpetrator's view.

Elizabeth Hartney demonstrates that, according to Cossins & Plummer (2016), the abuser may depend on the survivor to replay his/her original trauma as a sexually abused child, "Similarly, by becoming an abuser, someone who has been abused can play the role of the more powerful person in the relationship in an attempt to overcome the powerlessness they felt." Unfortunately, this is ineffective, and they may repeatedly dominate others in a futile attempt to overcome the weakness they experienced.

Mental Health Expert and award-winning Hollywood director, writer, and producer, John Callas (2023), explains, "It [Trauma Bonding] is a strange dynamic, but after being abused, the captor becomes a security for food, shelter, and in an odd way validation/love."

Licensed Mental Health counselor Stephanie Juliano, LPCC, (2021) expresses that Trauma Bonding can also happen in a domestic partnership situation and "is a type of attachment that one can feel toward someone who's causing them trauma. It brings with it not only feelings of sympathy, compassion, and love, but also confusion." She illustrates it as a cycle of "if I'm loved, I'm abused; it's my fault, and I need to please them." Juliano stresses, "Many don't even make the connection that they are, in fact, being abused."

Medical News Today (2020) states that Trauma Bonding may occur "in any situation that involves one person abusing or exploiting another," such as domestic abuse, child abuse, incest, elder abuse, exploitative employment, kidnapping/hostage-taking, human trafficking, religious extremism/cults, sports, etc.

It seems universal that Trauma Bonding is an unexplainable phenomenon where the victim develops some form of attachment toward the abuser if presented with a specific necessity. In his book, Choice, Dr. Shad Helmstetter explained in 1989 that very highly stressful and emotional situations and events cause massive amounts of electrical and chemical activity in the brain and override the less emotionally charged programs of everyday decision-making circuitry. The strongest and more emotionally charged program wins out, which may explain how a survivor (even though they may know better) may confusingly develop empathy and devotion toward the abuser.

Stockholm Syndrome is a form of Trauma Bonding, and according to The Cleveland Clinic (2022), "Stockholm Syndrome is a coping mechanism to a captive or abusive situation. People develop positive feelings toward their captors or abusers over time. This condition applies to situations including child abuse, coach-athlete abuse, relationship abuse, and sex trafficking."

How is male and female Trauma Bonding different?

There may be insufficient research to depict the differences between males and females regarding Trauma Bonding. Society seems to refuse to acknowledge that male survivors may bond with their abuser, especially if the abuser is male. Society fails to understand that Trauma Bonding is a survival, coping, or psychological response used to survive the days, weeks, months, or years of abuse. Dr. Jim Hopper (2020) describes it as the Neurobiology of Trauma, "a combination of various branches of brain science that help to explain common ‒ but commonly misunderstood ‒ ways that victims (a) respond during a sexual assault, (b) encode and store the experience in memory, and (c) recall these memories later."

Researchers are unsure why some people develop Trauma Bonding, and others do not. There are many theories and hypotheses:

One theory some evolutionary psychiatrists rely on is generational learned techniques that have been passed down and have become a natural human trait. Earlier ancestors were at risk of being captured and killed by rival tribes, and forming a bond with the captors provided survival chances.

Another theory stresses how emotionally charged the situation appears and how the victim adjusts their feelings when a flicker of kindness is presented to them by the abuser. Victims realize that working with and not fighting against the abuser could secure their safety in the long run. If the abuser presents expressions of kindness, the victim may develop a sense of gratitude and convince themselves of the abuser's humanity—and even feel genuine compassion, which they may interpret as love.

Hollywood has glorified this scenario where the victim (female) falls in love with the abuser (male). Beauty and the Beast illustrates how the prince was a victim himself when the Enchantress placed a spell on everyone in the castle, leaving the prince in a beast exterior to reflect his cruel inner manners. After the Beast catches a merchant taking one of his precious roses from his immaculate garden, he demands that the merchant or one of his twelve children return to the castle to pay for the debt of the stolen rose. Belle volunteers and becomes the Beast's captive. Although the Beast did not kidnap Belle, this is an example of Stockholm syndrome and Trauma Bonding. Belle experiences the Beast's cruelty, alienation, and isolation, but she also discovers the Beast's kinder side and develops empathy and feelings for him. Beauty and the Beast hide behind the moral that everyone should not judge someone on superficial qualities like appearances but should value the character and kindness within the person.

This fairytale classic emphasizes the masculine ideology that men have power and women are emotional and powerless. It also exposes Belle's inner faith and strength that love conquers all, even though she is held captive and forbidden to see or communicate with her family. During the storytelling, the audience develops empathy for the Beast along with Belle and rallies for him to open his heart before the last rose petal falls. Ultimately, we celebrate that the curse is over, the Beast is indeed a handsome prince, and he and Belle live happily ever after.

What is this story imprinting on the young people watching it? Is it okay to be held captive and separated from your life as long as the captor is genuinely a kind and handsome prince? Is it okay to abuse someone else since you were once abused? And the biggest question: is it okay to forgive someone for holding you hostage if the end result is true love?

Many people who experience Trauma Bonding are somehow holding out for the Beauty and the Beast happy ending.

I thought my experience would end the same. Like many survivors of Trauma Bonding, I was left confused and wondering what transpired.

My Story

I found myself in a position where I did not trust or feel safe in my home. At night, my father would sneak into my bed when drunk and call me his "pussyboy." My mother looked the other way and pretended it never happened.

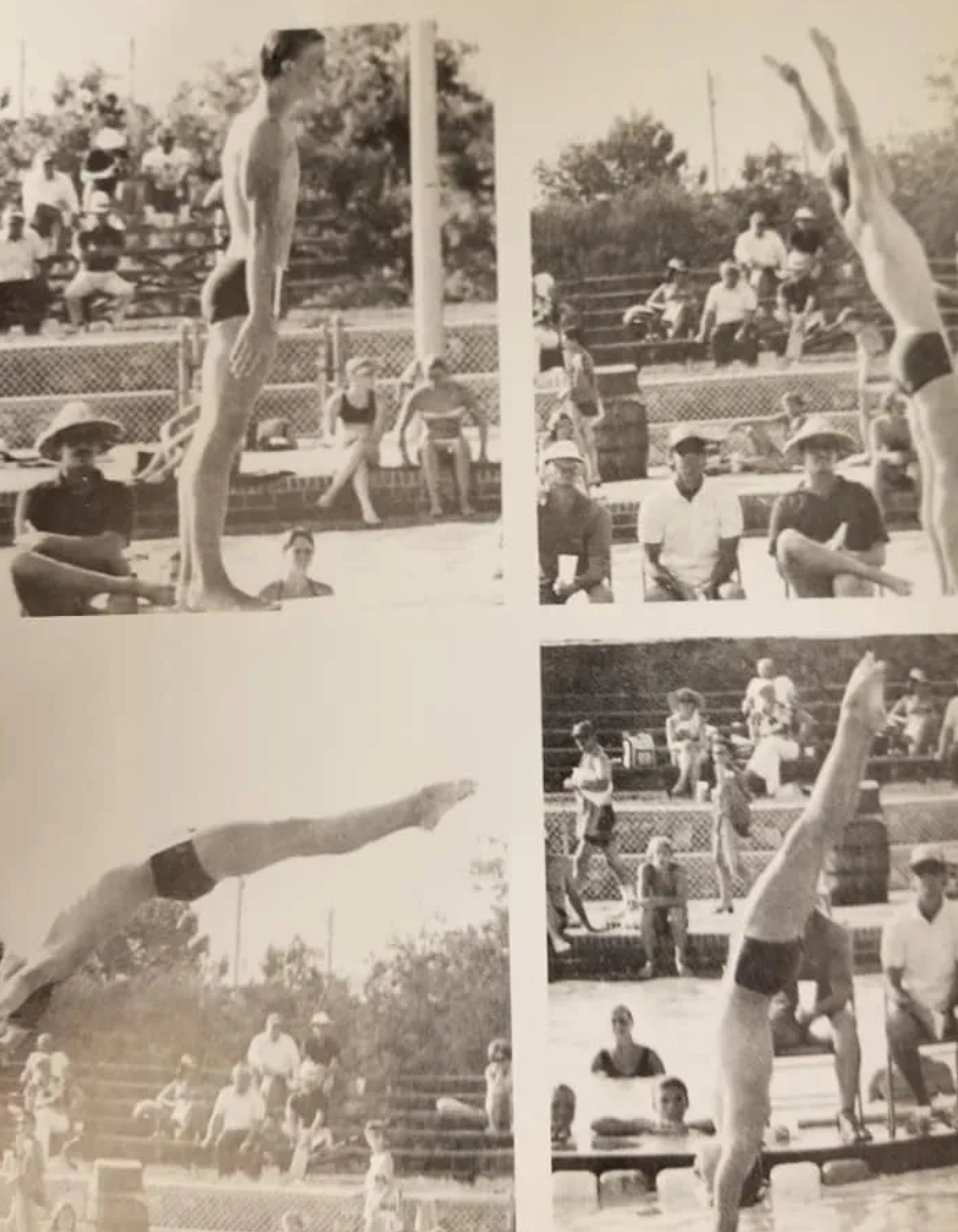

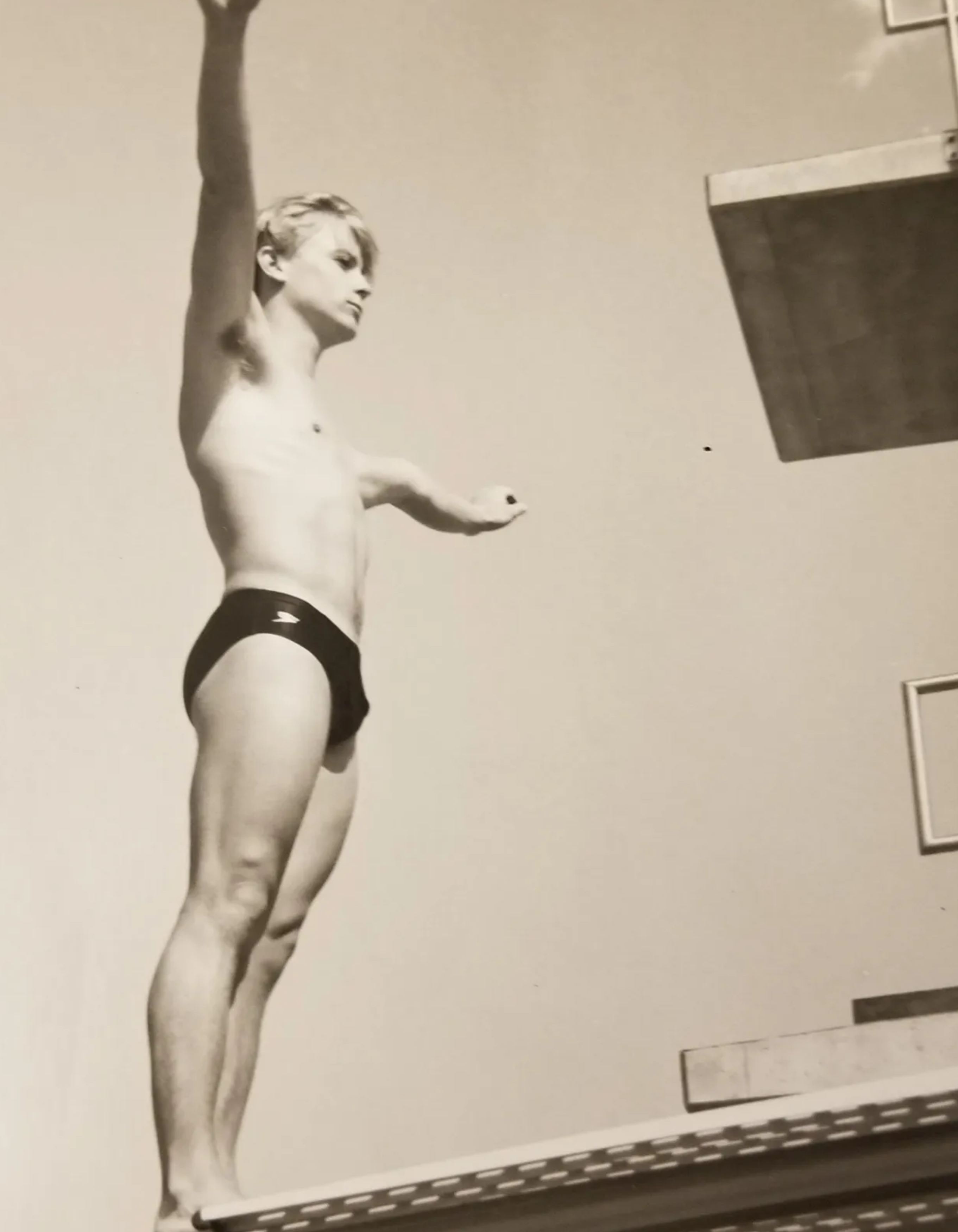

My situation became even more highly-emotional when I was fourteen and trafficked by a group of professionals that created the ruse that they were supporting and sponsoring my Olympic dream. My mother agreed with the professionals to prepare me for specific times and days. I felt confused, scared, ashamed, guilty, embarrassed, and utterly alone during these traumatic events. I felt there was no one to talk to or ask for advice. I was constantly told that I had to keep it a secret or there would be consequences.

My coach came to me one day and shared that he knew what I was going through, and I could talk to him. He started making time for me, and for the first time, I felt safe. The coach was extraordinarily handsome and closer to my age. I felt a brotherhood quality with him. He started picking me up in his red Mustang convertible to go to practices and competitions. We talked about music, plays, books, and movies. He introduced me to alcohol and encouraged me to let go. I trusted him and enjoyed being in his company. He began cuddling and touching me when we went on overnight trips to practice with the university team and his alma mater.

The touching led to him insisting on me doing other things. I struggled with not wanting to do what he asked and the fear of losing him as a coach and his friendship. I remember feeling wrong and guilty when it was over, lying there trying to understand what was happening and trying to separate the coach from the professionals. The professionals made me feel like property and unimportant, while I felt heard and essential by the coach. Then the coach would whisper in an alcohol-induced state, slurring his words, how he never felt this way with another guy and made me promise that no one could ever find out. I would instantly feel special and needed. Yet, the next day he acted as if nothing had ever happened. He exclaimed, "Man, I was drunk last night. I can't remember anything."

After the abuse from the coach started, he began treating me cruelly in front of the other teammates and at competitions. I felt betrayed, and my self-esteem diminished. Later, the coach told me he was sorry for how he acted and was trying to prevent anyone from finding out about our relationship. He wanted to keep it quiet and special—otherwise, it would become tainted with other people's judgments and ridicule. I would once again feel special.

The rollercoasters of emotions were quickly normalized as I found myself having deeper feelings for this coach. I didn't understand the feelings at the time, but I knew I felt the safest whenever I was around the coach. I decided to put up with the ugly comments during practices and at competitions, if I felt wanted and needed when we were alone.

This safe haven lasted four years of high school while the professionals continued trafficking me. I convinced myself that the coach gave me the strength to face every day. I misinterpreted his kindness and attention. The day I signed my commitment to college, he told me he was getting married and did not want to see me like that anymore. He said that it did not mean anything.

I was devastated and felt lost. My fairytale ended with me trying to figure out how to survive alone.

Later I learned that the coach was part of the professionals and paid to focus on me. I did not know at the time that he was once sexually abused.

Identifying Trauma Bonding

Amanda Kippert (2021) shared a list of signs of Trauma Bonding on DomesticShelter.com:

- You feel stuck and powerless in the relationship but want to make the best of it.

- You don't know if you trust the other person, but you can't leave.

- You'd describe your relationship as intense and complex.

- There are promises of things getting better in the future.

- You "focus on the good" in the person even though behaviors you know are abuse.

- You think you can change your abusive partner.

- Your friends and/or family have advised you to leave the relationship, but you stay.

- You find yourself defending the relationship if others criticize it.

- The abusive partner constantly lets you down, but you believe them anyway.

"The main sign that a person has bonded with an abuser is that they try to justify or defend the abuse" (Medical News Today, 2020):

- They agree with the abusive person's reasons for mistreating them.

- They try to cover for the abusive person.

- They argue with or distance themselves from people trying to help, such as friends, family members, or neighbors.

- They become defensive or hostile if someone intervenes and attempts to stop the abuse, such as a bystander or police officer.

- They become unwilling to take steps to leave the abusive situation or break the bond.

A person bonded with their abuser might say, for example:

- "He is only like that because he loves me so much — you would not understand."

- "She's under a lot of pressure at work; she can't help it. She will make it up to me later."

- "I will not leave him; he is the love of my life. You are just jealous."

- "It is my fault — I make them angry."

The feelings of attachment for the abuser do not necessarily end when the survivor leaves the situation. The survivor may still have feelings or love toward the abuser and may even desire to return.

Treatment

Each survivor is unique and needs treatment designed and tailored to their specific needs. What worked for one survivor may not work for another. Working with a specialist who knows that one process does not fit all is imperative. It is also important to note that the healing journey is a long-long endeavor.

Treatment for some survivors may include psychotherapy ("talk therapy") and medications if needed.

I found the most success with the Self-Talk Institution, where I focused on my internal negative self-talk and replaced them with positive self-talk. Understanding that everyone is groomed from birth and that the people and society around us influence us helped me recognize that I created negative self-talk to comprehend and understand why the abusive events happened in the first place. By changing my Self-Talk, I can change my programming, and by changing my programming, I can change my life.

About the Author:

John-Michael Lander is a Survivor, Advocate & Public Speaker

He is also the founder of An Athlete's Silence: www.anathletessilence.com

Published by SurvivorSpace, an initiative of Zero Abuse Project