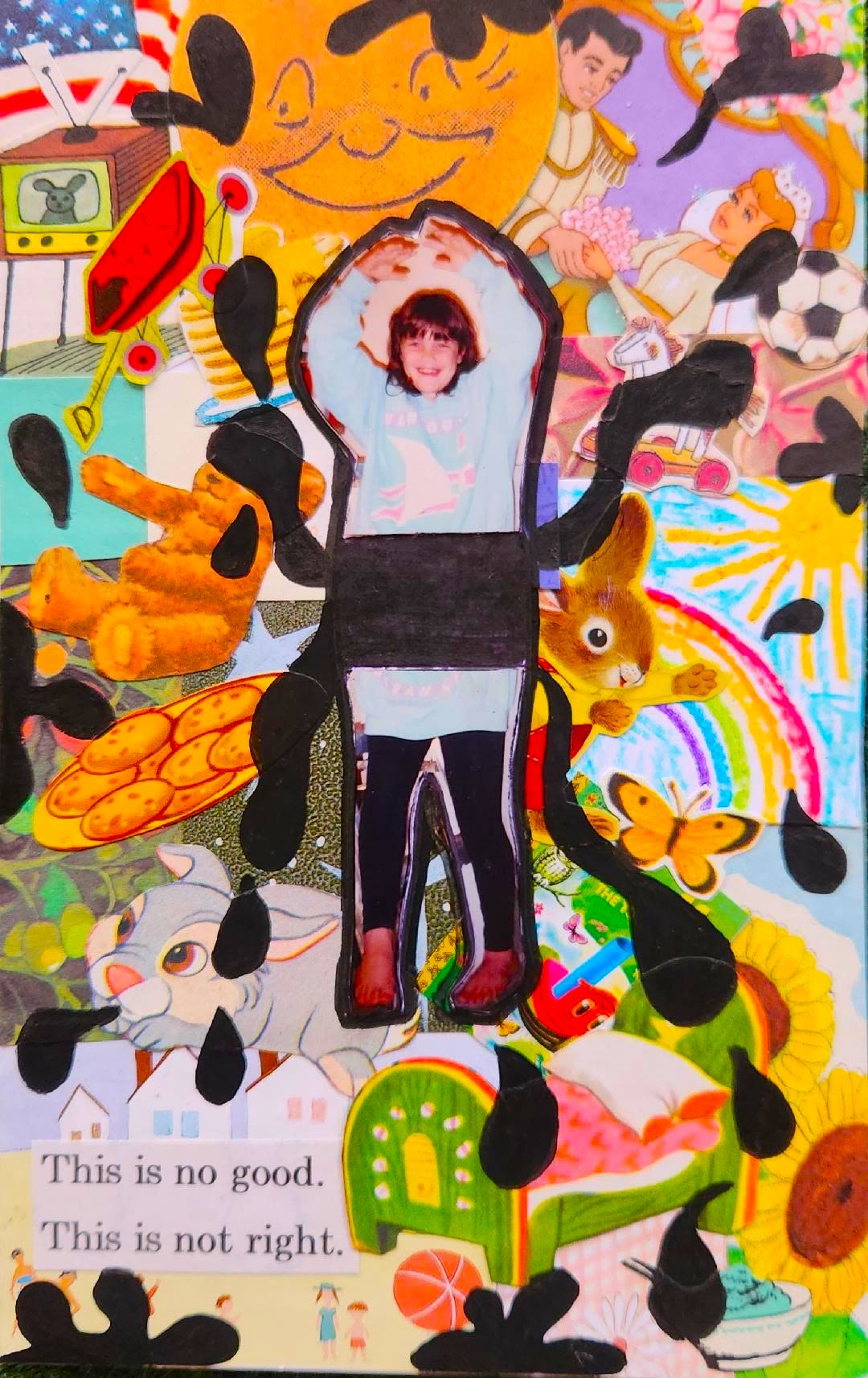

Keeping Secrets

We dance round in a ring and suppose,

But the Secret sits in the middle and knows.

-Robert Frost, “The Secret Sits"

Alcoholics Anonymous teaches our secrets keep us sick. Maybe that is why every now and then for over two decades, I would, out of nowhere, feel like my insides were crawling up into my throat. There was never a particular trigger, but I was keenly aware the feeling was my secret having grown legs, a spider trying to get itself out. I responded by swallowing hard, over and over, until I didn’t feel it anymore. My secret was the catalyst for much more than those moments of hard swallows. It accounted for huge portions of my instability, self-harm, depression, codependency and debilitating anxiety.

It wasn’t until my late twenties, after years of mostly unmanaged panic, a close friend proposed the idea that perhaps there was a connection between all my mental health issues and my secret. Looking back, it feels absurd not to have done the dot connecting on my own, years prior, but I didn’t. In that moment I was able to hear the suggestion without being defensive or dismissive. Her words, hovering over homemade pizza covered in artichoke, olives, sundried tomato, feta and oil, were the beginning of a long, miserable, magnificent journey towards healing.

I lived with my abuser from two to nine and visited his home every summer thereafter until about thirteen. I didn’t tell my parents about the abuse until I was twenty-eight. My mom and dad divorced when I was two, leaving my mom to work full time. My dad was running hard in another direction in attempt to get away from his own demons. I spent most of my time at a caregiver’s home (I called her Nanny). She happened to own the duplex my mom and I lived in. Our homes were connected, making it easy for me to come and go between them via a bedroom door, but spending most of my time on her side.

I don’t have a lot of vivid memories of the abuse itself, and I don’t suppose at this point I think details are important. Fact is, it happened, and it made me feel unsure, unsafe, afraid and filthy. My abuser was Nanny’s grandson. He was in his twenties at the time, a victim of abuse himself. He has a mental disability that prevents him from functioning beyond the level of a thirteen-year-old. She had gained custody of him when he was in elementary school, removing him from his father, her son. We spent time watching movies together, listening to music, talking about our favorite professional wrestlers, sharing meals, going to the pool, all the things you would do with a friend, because he was one of my closest friends.

As a kid I think the catalyst for not telling was a combination of confusion and not wanting to get him in trouble. I knew something about what he was doing around me, to me, was bad, but I didn’t understand how or why or what to do with that feeling. As I got older, I just got stuck harboring something I never wanted but didn’t know how to let loose. I didn’t want to tell because I didn’t want to burden anyone. I really believed I could just keep it locked up within me forever. I didn’t know what “trauma” was, much less how it snakes through your whole body wreaking havoc in every way. This was the nineties, so there were no TikTok clips to help me understand my entire personality was actually a trauma response. I had no language for anything. The only way I knew to manage the memories were by trying to forget them or convince myself it wasn’t that big of a deal to begin with.

My abuser was at every holiday event. I was in his wedding as an adult. He was part of my family. This contributed to how impossible it felt to tell, especially as year after year passed, and I was far removed from any continued abuse. I did have a little sister, who was born when I was thirteen, and at one time lived in the duplex next to him. I made sure he knew if he ever touched her I would kill him. That was the one and only time I ever let him know I knew what he did was wrong. Having a child young, my own son was occasionally in his presence. It was never unsupervised, and I never allowed him to hold my son. I had a lot of guilt and confusion about how to manage my own children sharing any kind of space with him.

At twenty-eight, finally taking myself to counseling to specifically deal with the abuse, the first thing I told my counselor was I would do whatever she wanted except tell my parents. What I didn’t know at the time but would learn after months of intense treatment, was telling my parents would be an enormous part of my healing, and theirs. They could never understand the level of struggle I dealt with, especially as a teenager. I was so incredibly sad, angry, running around with all the wrong boys and a handful of grown men, drinking, smoking, covered in cuts, blasting Marilyn Manson and Nine Inch Nails all hours of the day. Today I would just be some funny alt girl meme, but back then I was weird and very much on the fringe of what was considered “normal teen.” When I told them about the abuse, they were able to make sense of the person I was then, and the person I had become, especially considering the level of mental illness I was dealing with at any given time.

Speaking my secret to the people who needed to hear it most was one of the hardest things I ever did. I knew both my parents and my Nanny would on some level blame themselves, and there was nothing I could do or say to make it not so. That wasn’t my responsibility. Healing myself was my responsibility. So, I finally let the spider out of my throat. I let it crawl out of me and onto three people I love dearly, and who I know love me back just the same. I didn’t try to catch it. I didn’t try to flick it away. I just let it be whatever it was going to be. No more secret to keep me sick.

Original artwork by Brooks Decker

Published by SurvivorSpace, an initiative of Zero Abuse Project.